New England Realty Associates - NYSE:NEN

The Colonial Deal

In the 1970s, there was a criminal-run investment group called Colonial Realty. Colonial oversaw three partnerships that owned about 6,500 apartment units around New England.

Lured by promises of 11% annual returns, more than 7,000 investors poured $35 million into the Colonial partnerships.

Colonial heavily leveraged its portfolio and ultimately went bankrupt in 1974. A forensic review of accounts revealed that of the $18 million raised for certain partnerships, only $2 million was used to buy property. The remaining investor funds “dissipated elsewhere.”

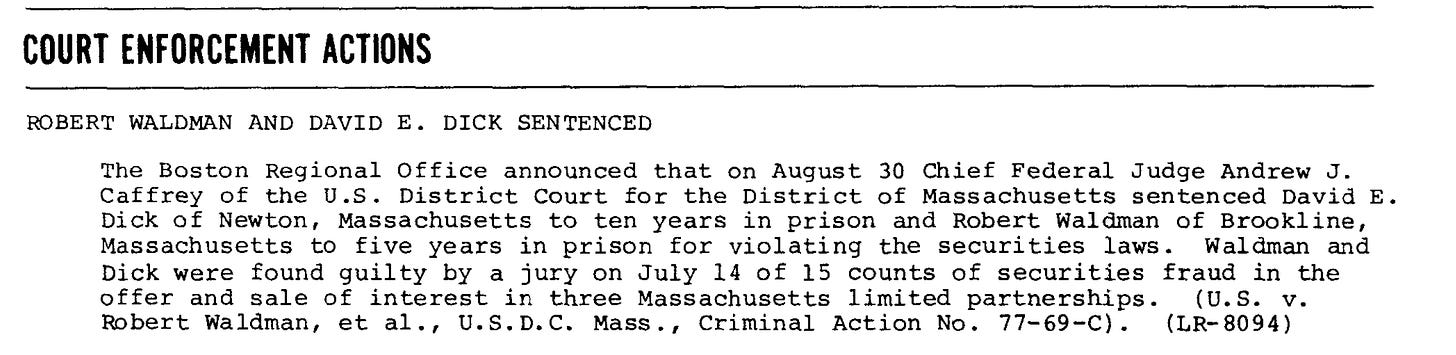

Colonial’s general partners David Dick and Robert Waldman were convicted on 15 counts of securities fraud and received prison sentences of 10 years and 5 years, respectively.

The trustee of the bankruptcy estate worked his way through creditor negotiations and bank foreclosures. In a relatively short period he sold ~5,000 apartment units and satisfied enough creditor claims to put Colonial in a position to emerge from bankruptcy.

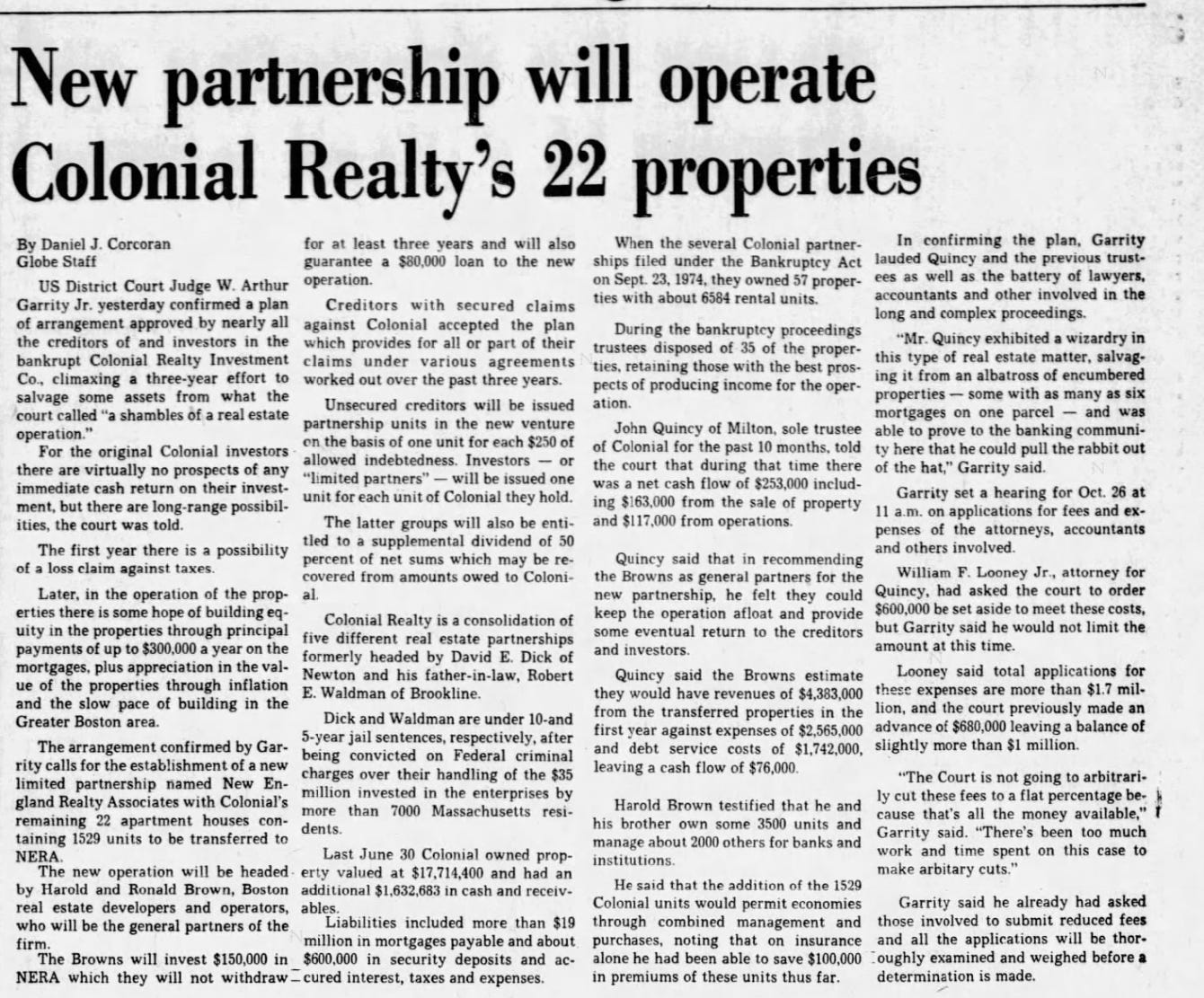

In 1977, three years into the reorganization, brothers Harold and Ronald Brown stepped into the picture.

Harold Brown was a graduate of M.I.T. and a U.S. Navy veteran that served in both WWII and Korea. He worked as a chemical engineer for more than a decade and began investing his savings alongside his brother Ronald to redevelop properties around Boston.

Gifted with dealmakers’ instincts, the Browns would turn empty basements into apartments and divide single apartments into two or three units. They saw value where others didn’t, and their playbook was simple: buy underperforming or underutilized properties, renovate, refinance, and move to the next project.

Harold purchased his first 6-unit building in 1954. By 1977, the Brown’s Hamilton Company amassed a portfolio of ~3,500 apartment units, and managed another 2,000 apartments for banks and other clients.

The Browns pounced on the Colonial deal. Harold and Ronald contributed only $150,000 (~$800,000 in today’s dollars), guaranteed an $80,000 loan, and issued equity to unsecured creditors. The Hamilton Company took control of the remaining 1,529 apartment units owned by the bankruptcy estate.

When the plan was finalized, the Colonial partnerships emerged from bankruptcy under a new banner: New England Realty Associates (“NERA”). NERA would enable the Browns to expand their real estate empire and provide creditors the opportunity to make their money back. It was a win-win for all involved.

The NERA equity issued to Colonial’s creditors was publicly listed in the late-1980s and currently trades on the NYSE under the ticker symbol “NEN” and is organized as a Master Limited Partnership1.

Harold Brown retired in 2018 and passed away in 2019 (his obituary on the Hamilton Company website can be found here.) By all accounts, Harold was a family-oriented man, shrewd operator, and someone that cared deeply about his community.

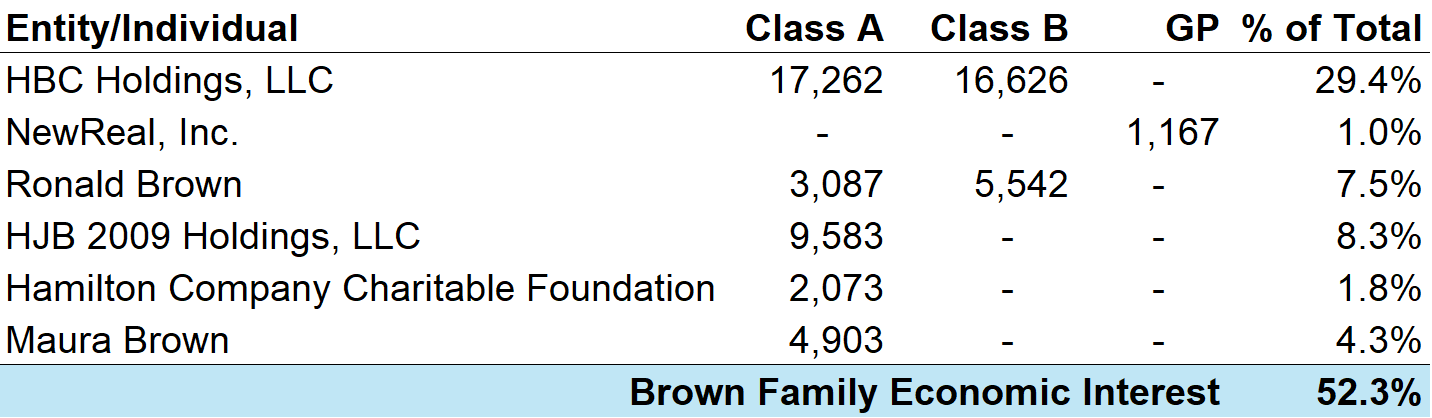

NERA and its affiliate, The Hamilton Company, are now led by Harold’s son, Jameson Brown. The Brown family owns >50% of NERA across multiple entities and share classes:

The Merchant-Owner

As we learned from the Colonial case, the capital intensity and cyclicality of real estate lends itself to over-leveraging and short-termism. For most sponsors, long-term ownership isn’t a viable business model.

Your typical real estate investment company is beholden to the Merchant’s Treadmill:

To keep the lights on, they must keep doing new deals, regardless of market conditions. To bankroll new deals, they must exit existing ones. And around it goes.

Most real estate sponsors organize their business around acquisitions and development, their profit centers. Profit sharing (aka promote) is typically paid after capital events: refinances, recapitalizations, or sales. This structure encourages operators to sell newly built/renovated properties as soon as possible, crystallizing profits to cover pursuit costs and GP equity requirements for the next deal.

This misalignment of incentives ensures that bad deals get funded on the way up, and developers/sponsors implode on the way down. Some overextend themselves to make deals work when skies are blue: overpaying for property, taking on high-cost bridge loans, getting cute with personal guarantees, and so on. Downturns expose those mistakes.

The Investor-Owner

New England Realty Associates is a different animal. Its whole ethos is long-term stewardship, opposite of the merchant-owner “turn and burn” mentality.

For instance, NERA still owns about a third of the apartments it acquired out of the Colonial bankruptcy. Most real estate operators wouldn’t hold a property for five years, let alone fifty.

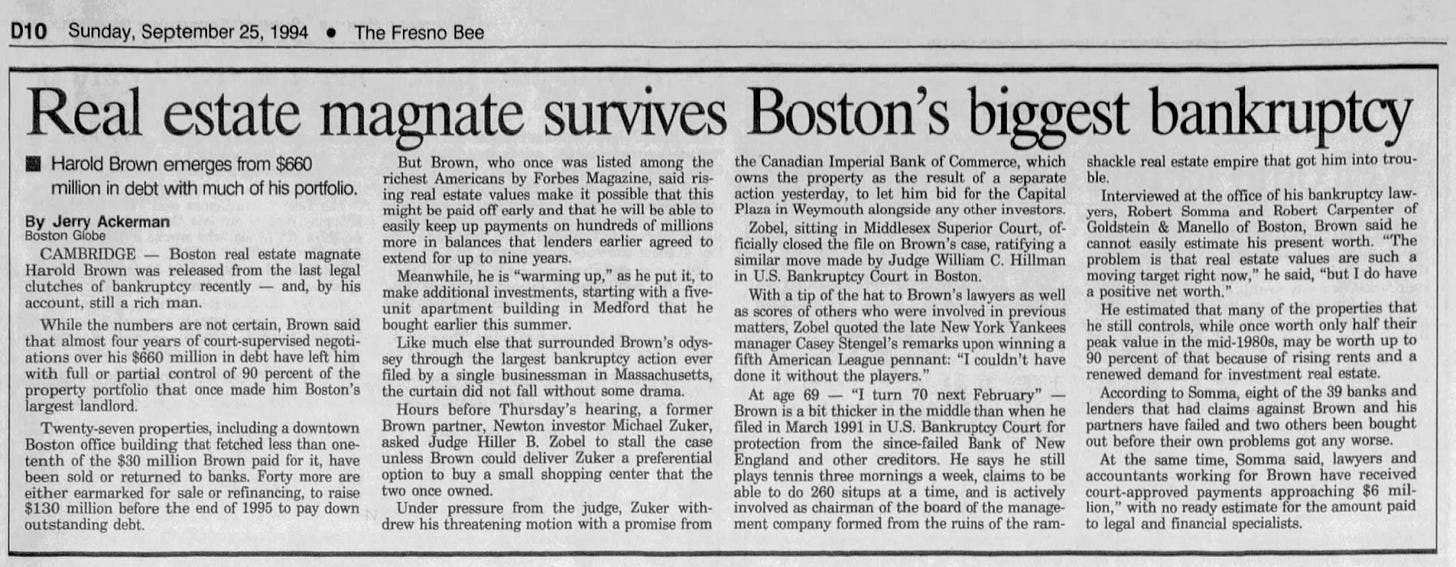

But long-term stewardship and conservatism weren’t always part of NERA’s DNA. It took a painful lesson. In the early 1990s, Harold Brown voluntarily filed for bankruptcy with a reported $675 million of debt.

Bankruptcy permanently reshaped how he thought about growth. Harold became far more suspicious of aggressive leverage, short-term flips, and deal structures that forced quick exits. After reorganizing, Harold rebuilt more deliberately, favoring durability and balance-sheet resilience, even as special opportunities came about.

The experience taught him that scale without prudence in the real estate business is fragile. Steady, long-term growth backed by a conservative capital structure is what wins in the long run. I’ve even heard NERA referred to as the Brown family’s “anti-blow-up investment vehicle.”

The New England Portfolio

NERA’s investment strategy is rather simple; it specializes in Class B and C workforce housing. It acquires, maintains, and improves well-located, mid-market properties that would be difficult to replicate.

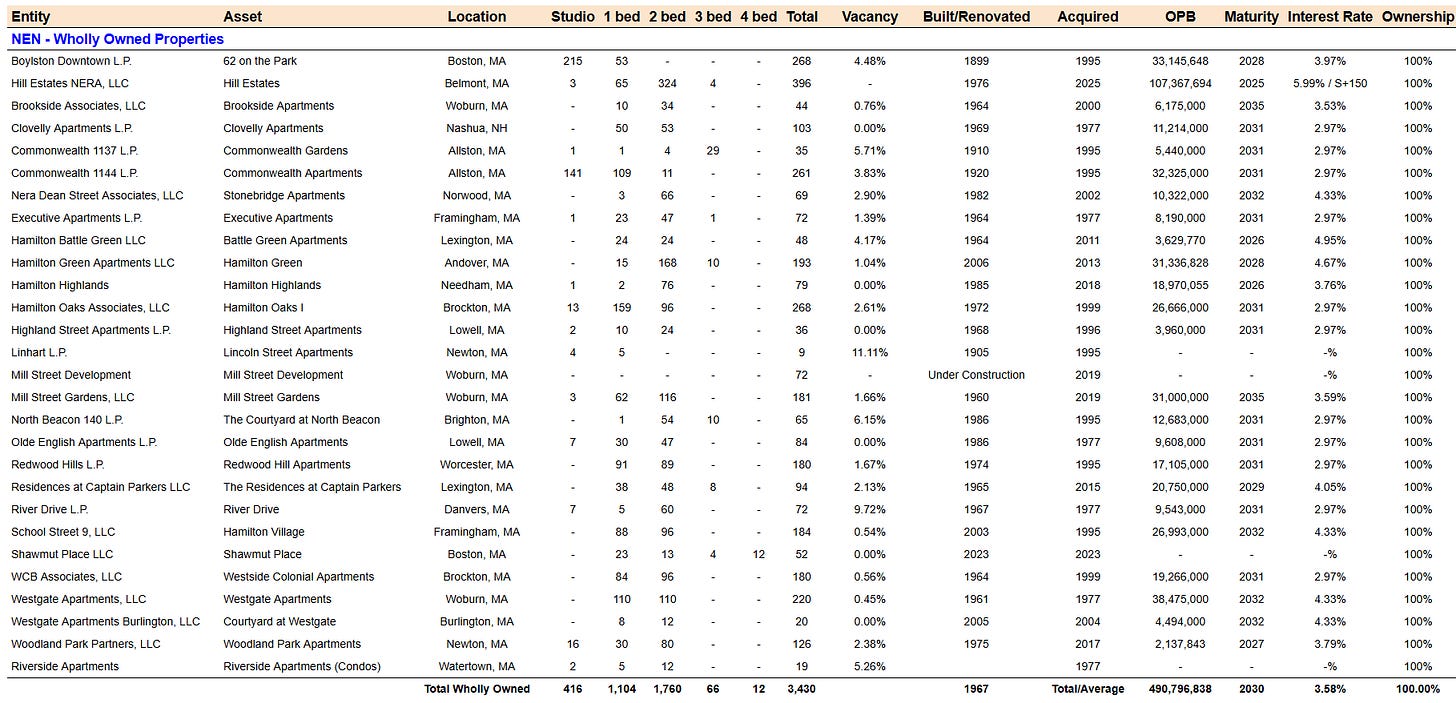

The portfolio consists of 3,411 apartment units, 19 condos, and about 159,000 square feet of commercial space. It is concentrated in Eastern Massachusetts, with one property in Southern New Hampshire:

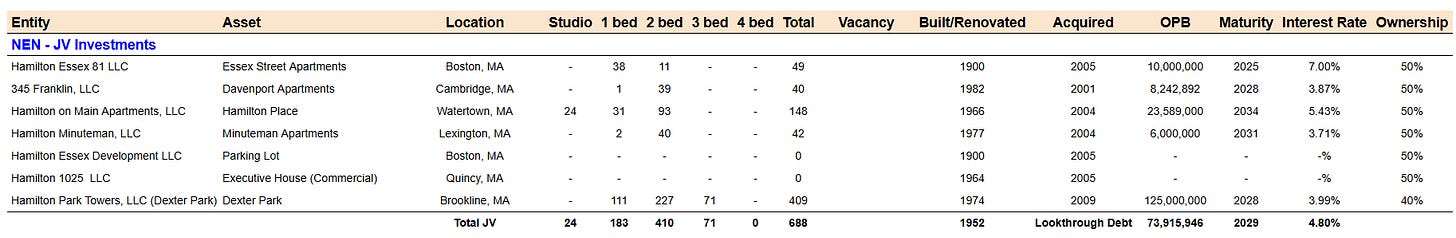

NERA also owns a 40 - 50% interest in 7 joint venture (JV) investments, with the Brown family and/or Hamilton employees owning the other 50 - 60%.

The JV portfolio includes 688 apartment units, 12,500 square feet of commercial space, and a 50-car parking lot. NERA’s affiliate, The Hamilton Company, serves as property manager for the portfolio and joint venture investments.

A few examples of NERA properties and how it came to own them:

62 on the Park - Boston, MA - purchased in foreclosure auction from a lender for $1 million, previous owner converted it from a hotel.

Dexter Park - Brookline, MA - acquired from UBS during the financial crisis.

Hill Estates - Belmont, MA - purchased from third generation family owner that built the community ~60 years ago.

Supply-Constrained Market

Boston and its surrounding towns are much like San Francisco or New York City: it’s incredibly cumbersome and costly to build new housing. Construction costs have risen so dramatically that developing luxury Class A buildings is often the only option that makes economic sense. This dynamic leads to a natural undersupply of market rate Class B and C housing stock.

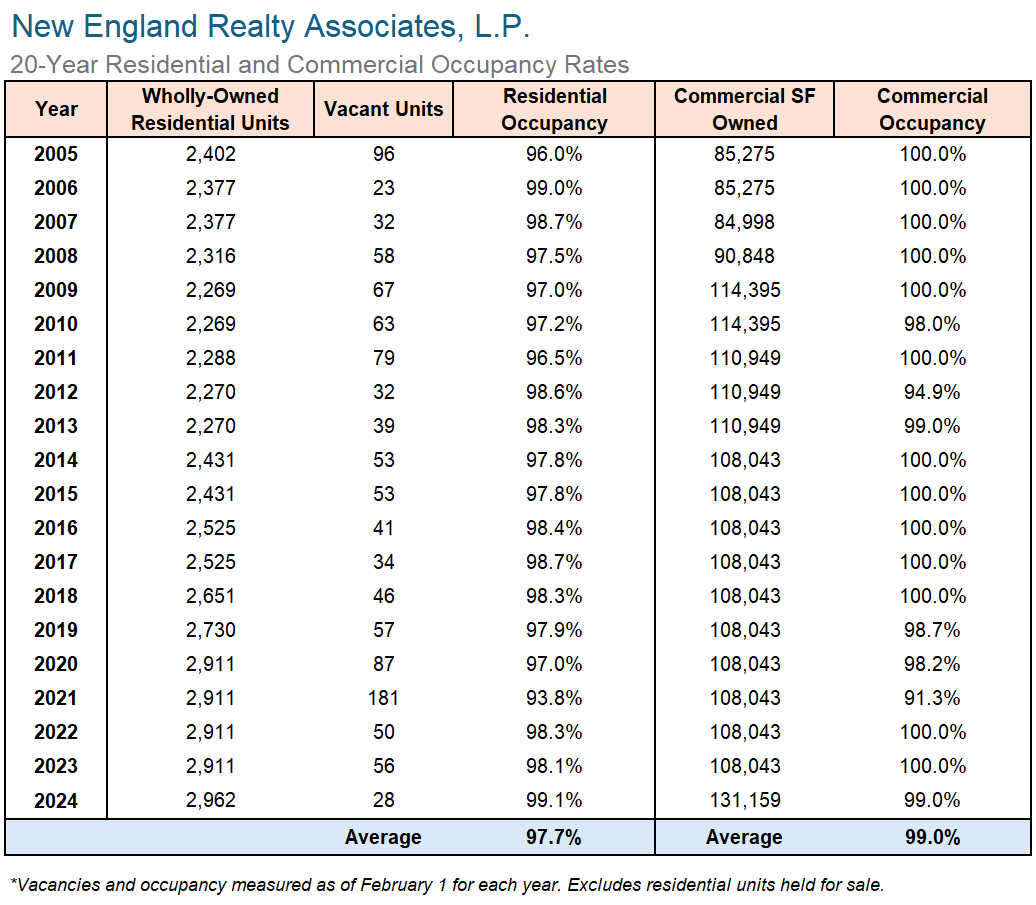

Rising home-ownership costs have also pushed more households into renting, a favorable tailwind for NERA. The supply/demand imbalance allows it to maintain high 90s occupancy with consistent upward pressure on its rental rates.

What’s it All Worth?

I think you should look at the value of NERA from a few angles: as a standalone business, the replacement cost of its assets, and what it might be worth to an acquirer.

NERA NOI for the last twelve months was about $56.4 million if you include $7.0 million proforma NOI from the Hill Estates acquisition and about $7.0 million of look-through NOI from the JV investment portfolio. I think NOI of $60 million is a realistic target for the next twelve months.

Let’s assume NERA has another steady year of >95% occupancy with modest rental rate growth. That might be >$1 million of incremental NOI.

We also have 72 new apartments at the Mill Street development coming online in November. Perhaps Mill Street can contribute ~$1.5 to $2 million of NOI upon stabilization.

Lastly, the community upgrades and renovations at the 396-unit Hill Estates may drive NOI another >$1 million in 2026. NERA has supposedly renovated 40 or so units, or approximately 10% of the property at the time of this writeup.

With $564 million of net debt (including unconsolidated JV net debt) and a ~$242 million market cap, NERA trades at a ~7.5% cap rate on my 2026 estimates, and about a 10% levered free cash flow yield.

Replacement Cost

A recent study showed construction cost estimates of $550K/unit for mid-size market rate multifamily projects in Boston. While I’m not married to the $550K figure, it sounds reasonable.

A Zillow search for condos and townhouses with >750 SF in the greater-Boston area yielded about 1,350 listings. Only 100 of those homes were listed below $550K.

Even if we haircut the estimate and say replacement cost is closer to $500K for more suburban properties, NERA still looks cheap: replacement cost would be about $1.8 billion. At a current EV of $806 million, NERA trades a >50% discount to estimated replacement cost.

What’s it Worth to an Acquirer?

The prevailing cap rates for Class B multifamily properties in greater-Boston are reportedly in the 5.5% to 6.0% ballpark. If we take the midpoint of the range at a 5.75% cap rate on 2026E NOI of $60M, the NERA portfolio would be worth approximately $1.04 billion.

Subtract out the debt, and you’re left with an equity value of about $479 million, or $137 per unit. That estimate ignores transaction costs, but it also doesn’t give any credit to NERA’s below-market mortgages. NERA’s existing debt may help it negotiate a more favorable “headline” cap rate.

An acquirer may want to buy NERA’s portfolio to take advantage of the interest rate arbitrage. In other words, if a buyer were to put new debt on NERA’s assets today with 10-year fixed-rate mortgages, its effective interest rate would be closer to 5.0% or 5.5%.

Our theoretical buyer could assume some or all of NERA’s mortgages and capture a spread of 80 to 130 bps relative to current interest rates. That may not seem like a lot, but a 1% difference would translate to ~$5.5 million of interest savings per annum.

As a sanity check on property values and leverage ratios, I encourage readers to check out the valuations of select mortgaged NERA properties here in Exhibit A. According to its lender, most LTVs are in the low-50% range on its Master Credit Facility.

Closing Thoughts

No matter how you frame it, NERA looks undervalued. Its portfolio has been steadily occupied in the high 90s for the last twenty years, including the COVID pandemic and GFC. It is conservatively financed with a long-term mortgages at a weighted average interest rate of 4.2%. Earnings continue to grow, and the properties will benefit from the Class B and C supply/demand imbalance for the foreseeable future. As for skin in the game, the organization is led by a family that owns more than a 50% economic interest in the business. I look at NERA and see a mispriced stock with the potential for its real estate to be worth much more over time.

Why Does the Opportunity Exist?

Screens poorly

Unloved MLP structure

No sell side coverage, relatively undiscovered outside of value stock circles

Small float & ADV

Potential Catalysts

Share repurchases

REIT or C-Corp conversion

Takeover or management take private/recapitalization

Large asset sales or refinances (Hill Estates, Boylston, Dexter Park, Commonwealth, Hamilton Oaks, etc.)

Risks

Interest rates: near term maturity of Hill Estates bridge loan, and largest JV mortgage due in 2028 (Dexter Park, $125M)

Liquidity crunch (e.g. an event that requires immediate and substantial cash investment; not covered by insurance)

Regulatory changes (rent caps, eviction moratoriums, etc.) negatively affect property values.

Non-controllable expense inflation: property taxes, insurance, permits, fees, non-pass-through utilities.

Master credit facility covenant breaches or cross-default

Disclosure: I own NEN

DISCLAIMER: NOTHING IN THIS WRITE UP SHOULD BE CONSIDERED INVESTMENT ADVICE. I MAY BUY OR SELL SHARES/UNITS OF THE PROFILED COMPANY. ILLIQUID STOCKS CARRY SIGNIFICANT RISK. PLEASE CONSULT A FINANCIAL ADVISOR AND DO YOUR OWN DUE DILIGENCE.

Sources & Further Reading

SEC Filings

https://www.bostonmagazine.com/uncategorized/2006/05/15/the-comeback-kid/

https://www.bostonherald.com/2019/02/24/rabbi-storied-boston-landlord-harold-brown-dies/

https://www.thehamiltoncompany.com/About-us/Press/once-burned%2c-twice-(not-so)-shy?relId=2636

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/579/649/126744/

https://www.thehamiltoncompany.com/About-us/Press/harold-brown-obituary?relId=4057

https://nerej.com/harold-brown-stepping-down-as-chairman-of-the-hamilton

Partnerships | Internal Revenue Service - https://www.irs.gov/businesses/partnerships

It was high 6% almost 7% cap on the reported NOI so not tax adjusted. I’ll look at NEN further. Thanks for the article and the response!

I am getting closer to an 8.3 cap (incl pro-rata JV NOI, debt, and subtracting construction at cost). Interesting perspective on Hill Estates renovations; gives hope that this was not a bad deal. I was concerned about the recent vacancy step-up combined with much higher leverage following the Hill Estates deal. Do you have any thoughts about the post-renovation implied cap rate of the Hill Estates deal?